The History of Glacier House

The History of Glacier House

John Marsh authored this in April 1970 for the Golden & District Historical Society

The completion of the Trans-Canada Highway through the Selkirk Mountains, via Rogers Pass in 1962, has enabled thousands of tourists to visit Glacier National Park. Likewise, at the turn of the century, the railroad encouraged people from all over the world to visit and stay amidst the alpine splendor of the central Selkirks. The focus of the recreation facilities developed by the Canadian Pacific Railway in the area of Glacier House. It began as a dining lodge in 1886 and then underwent various stages of development as a hotel before closing in 1925.

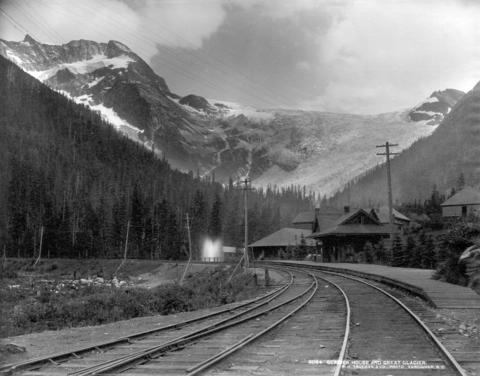

When first constructed, in the 1880’s, the railroad passed over the summit of Rogers Pass and on the west side looped into a series of valleys, thus giving a workable grade. At the head of the first loop, two miles west of the pass, the line crossed the Illecillewaet River, near the present campground. The original Glacier station was located on the curve immediately west of the river. The hotel complex was built on a small flat adjacent to the station and within two miles of the Illecillewaet, or ‘Great,’ Glacier.

The C.P.R. began regular coast-to-coast services in 1886. To avoid hauling heavy dining cars over the pass, it was decided that dining facilities should be provided at Glacier. Accordingly, in 1886, a dining car was parked permanently on a siding by Glacier Station. Mr. Wharton supervised the crew which provided meals for the passengers on the two daily trains. Meanwhile, a permanent dining lodge was constructed and opened the following year. It was a square, wooden building, placed next to the station and consisted of a large dining room, reception area and six bedrooms. The building was similar to the Mount Stephen House and Fraser Canyon Hotel and was generally considered to be in the Swiss chalet style.

Mr. Perley was appointed as the first manager. A register was provided and the first guest signed in on 18th January, 1887. That year, 708 guests registered but in 1888 the number increased to 1020, thus putting the place under some pressure. Rev. Green, one of the most famous of early guests, noted: “On one occasion when we returned from an absence of several days in the mountains, we found that besides our room being occupied, our two spare tents had also been pitched to give sufficient accommodation. After that, a sleeping car was brought up and left permanently on a siding to accommodate the occasional overflow from the house.”

The hotel was licensed and contained a wine cellar that Rev. Green used as a darkroom for printing the photographs he took on his climbing excursions. The staff consisted of Mr. Perley, his wife and niece, Mr. Hume, the secretary, a French cook with a Chinese assistant, three waitresses and a bell boy. Also, about the place were a black bear cub, a cat, some fowl and the hotel dog, Jeff.

In 1889, the proposals were made to expand the hotel. A Mr. Withrow recalls: ‘the manager told me that a large new one (hotel) was to be built shortly; fishponds and gardens were already being planned, but I am glad to see the place before these contemplated changes are made, for its natural charm and beauty will not be improved by them.”

In 1890 a new annex was begun, located adjacent to, but up the valley from, the first building. It cost the C.P.R. $9, 524 in 1890 and $7,0302 in 1891, and provided about 30 extra rooms. During this period, Mr. Perley left Glacier House to become manager of the Hotel Revelstoke. He was replaced by Miss Jean Mollison, formerly of Mount Stephen House. However, because of ill health, she was forced to retire and was replaced in 1893 by Mrs. Julia Mary Young of Montreal. Mrs. Young stayed for many years, being assisted by Miss McGibbon, and Mr. Wales as head waiter.

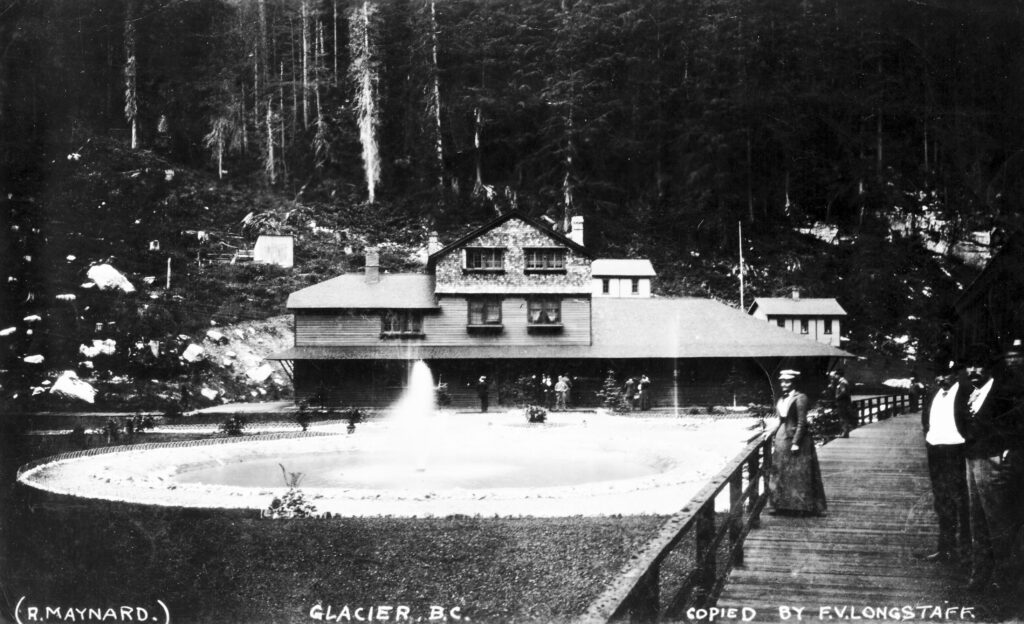

In 1895, there were over 700 guests, about half from the U.S.A. One guest from Europe noted: “The hotel is a pretty little chalet, mostly dining room with a trim level lawn in front containing a fine fountain.” A grizzly bear was chained near the station, along with a black bear. Jim, an American from Missouri, served as guide at the hotel for $3 per day. When not employed as a guide, he shot game for the hotel kitchen. A Stony Indian with his wife and child had a teepee on the hotel grounds. They provided a few horses for guests in return for a subsistence living. When they arrived or left is not recorded.

Of all the natural features in the area, the ‘Great’ Glacier proved the most interesting. One enraptured guest even enquired if it had been put there by the railway company. As hiking and climbing in the area increased in popularity so did the need for guides. Peter Sarbach was the first one to come from Switzerland, to climb in the Selkirks. He brought out a party of climbers from the Alpine Club in 1897. Many natural scientists came to study the glaciers, rocks and flowers of the area. They were encouraged to record their findings in a Minute Book for Scientific Observations, started in 1898. This book has been lost without trace but fortunately many of the scientists wrote up their studies in other scientific journals of the day.

In 1899, the C.P.R. brought out two Swiss guides, Christian Haesler, Sr., and Edward Feuz, Sr. Following a summer of climbing and guiding, and discovering new routes at Glacier, they both returned to Interlaken for the winter. In 1900, there were four guides at Glacier: Karl Schluneggar, Fredrick Michell, Jacob Muller, and Edward Feuz. The following year the number increased to six and throughout the decade a variety of guides moved between Switzerland and Glacier and the other mountain resorts. After a while, some stayed during the winter to serve as caretakers at the Glacier House.

In 1901, Arthur Wheeler, a renowned government surveyor and frequent visitor to the Selkirks described the hotel thus: “At Glacier House the large dining room opened off the lounge and the constant flow of people, to and fro, had worn a depression beneath the entrance doors, leaving a space under them; the floor was stained a dark oak colour. Electric light was furnished by water power from the nearby Asulkan Brook and was generally somewhat dim.” The remains of a dam on the Illecillewaet River and decayed wooden pipes can still be found in the vicinity of the hotel site. In 1901, the trains still stopped to allow passengers to obtain a meal, at 75 cents, or a room for $3. The hotel had a number of amenities which the C.P.R. eagerly advertised: “At the hotel are many sources of amusement for guests – billiard hall, bowling alley and swings for the children. An observatory has been erected, and a large telescope been places at the hotel. There is a dark room for photographers.” Ponies were also available at various rates according to the journey undertaken, likewise the guides could be hired at a fixed rate per day.

Mrs. Young was invariably recognized as an excellent hostess but there were a number of complaints made in the visitors book in 1905 and 1905, for example: “To make the Glacier Hotel (as it should be) the beauty spot of the Dominion, better provision should be made for supplying the cravings of the “inner man”, i.e., dining room accommodation.” “The hotel is mist comfortable in every respect but with one exception, a comfortable smoking room for gentleman is badly needed and I daresay by the time we come this way again the needful will have been supplies.” “My room in the garrett is all right on one side but you bend on the other. A new hotel will do much to comfort guests, with fair prices this will be one of the most popular summer resorts.”

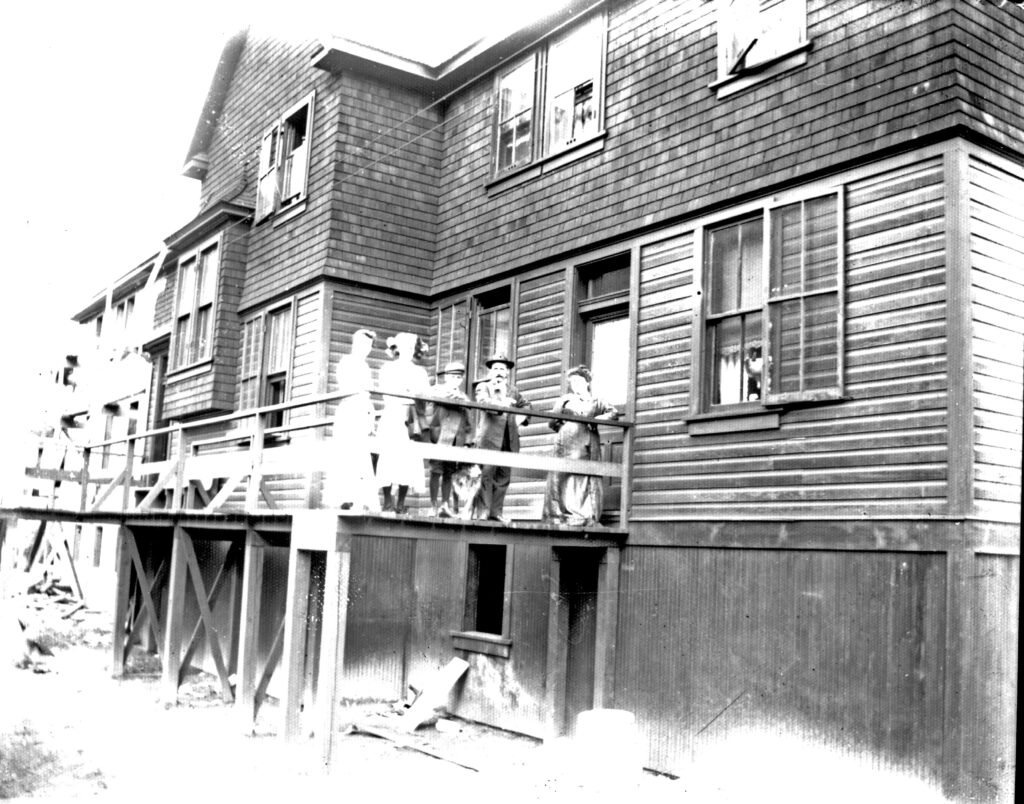

Probably as a result of the pressure on existing facilities and the complaints, a new wing was built, in 1906, up valley from the annex. The new unit contained 54 rooms with baths, radiators and an elevator. The hotel unites were all connected to each other by a covered verandah overlooking lawns and gardens. The hotel now totaled 90 rooms and rates had been increased from $3 to $3.50 per day. The wooden chalet style was retained and while some considered the place luxurious it was also noted that: “The decorations were far from elaborate – walls covered with mountain pictures, and rocks, mineral samples and flowers around made for a homey atmosphere.”

In 1912, 5419 people registered at Glacier House, which at that time could accommodate 150 people. The majority of guests were wealthy business and professional people from the United States, some visiting Glacier as part of a world tour. Most stayed a few day and took advantage of the trails, guides, horses and huts to visit the Great Glacier, the Nakimu Caves and the peaks around Glacier. Excursions were often done in style, one family visiting the Asulkin Pass noting: “It was noon when we arrived at the summit both tired and hungry. We set out our luncheon on a knole of rocks nearby and quaffed our champagne to the health of the first white lady who had climbed to this lovely spot to enjoy one of the most superb mountain views in the world.”

From 1912 to 1925, the two permanent guides at Glacier were Ernest Feuz and Christian Haeslar. By this time, many of the guides and their families were staying in Canada permanently so the C.P.R. constructed the chalet village of Edelweiss, near Golden, to accommodate them. Several members of the Feuz family still live in Golden, though not engaged in guiding. Mrs. Harding of Vancouver, who worked at Glacier House from 1914-1916 has provided details regarding the resort at that time. Mrs. Young was manager, and Mr. Wales headwaiter. There were 6 other waiters, a wine clerk, Chinese cooks and 10 chambermaids, who received $16 per month. Alf Thorn was the baggageman and George Ball, the handyman, from 1909-1925. The hotel was now open in winter, when a little skiing was carried out, but the annex and wing were not used.

Elizabeth Parker in her guide to Glacier, published in 1912, writes: Mr. Sydney H. Baker is the company’s outfitter at Glacier. He has on hand twenty well-trained and perfectly safe saddle and pack ponies and two pong guides. Mr. Baker also ran a curio tent, set up near the station platform, where photographs, guidebooks and souvenirs could be purchased. In 1920, he left but his wife maintained the business until 1925.

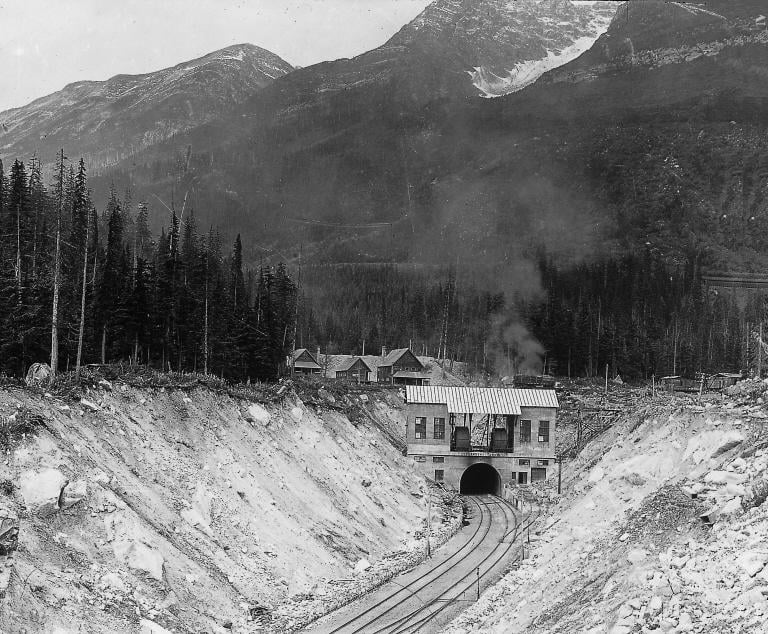

In 1916, the Connaught Tunnel under Rogers Pass was completed and the railway rerouted, thus reducing the grade and avoiding many of the hazardous avalanche areas. This placed the Glacier hotel just over a mile from the railway and new station. A road linked the hotel and station and passengers were transported along it by Tally-Ho. While the decline of Glacier House cannot be attributed to the rerouting of the railway, it did mean that trains could now carry dining cars, hence the function of the hotel as a dining room became obsolete.

The war had an impact on the tourist trade but in 1920 the hotel managed to attract nearly 4000 guests. Rates, by then, had increased, rooms being $4-$6 per day, guides $5 and ponies $3. Mrs. Young retured as manager that year and moved to Victoria where she died five years later.

In 1922, the Glacier House accommodated 3792 people. They still arrived by railway, for apart from a few scenic roads, such as that to the caves, there was no outside road access. The hotel structure had been facing the rigorous winters for several decades by this time so it is not surprising to find mention of repairs in 1922, in the Revelstoke Review: “A lot of renovating has been done at the Glacier Hotel this season and the fresh paint on the buildings adds greatly to their appearance.”

The repainting was like a swan song for 1925 was the last season the hotel was open. Mr. Oscar Dahl, the manager that year, closed the place for the last time on September 15. Caretakers, Hans Pieren of Adelboden and a Mr. Downie, remained at the hotel during the summer of 1926. Ed Feuz was reputedly offered the hotel for $1 but he declined and with the other Swiss Guides continued service at Lake Louise.

For some time, people expected the hotel would reopen and Major Longstaff, in 1930, thought that it was “the intention of the C.P.R. hotel department to erect a modern stone mountain hotel of some 200 rooms as soon as possible.” Indeed, rows of cement pillars at right angles to the annex had been laid as a foundation for an additional wing, and apparently blue-prints had been prepared.

In 1928, Wheeler commented in retrospect: “The chief charm of the hotel was into homelike atmosphere and the informal hospitality that led to a fine feeling of camaraderie and good fellowship. It is deeply to be regretted that for the time being the hotel is not in operation and that climatic conditions have caused the present building to be condemned.

There is not enough information available to indicate a single, precise reason for closing and not rebuilding the hotel; however, it seems likely that the following factors were involved. The structure was old and required expensive renovation, and, as recently had been demonstrated at Banff and Lake Louise, such buildings were a fire hazard. Lake of road access to Glacier, in an age of increasing car travel, meant that the area was unlikely to attract as many people as previously, especially as there were no large centers of population in close proximity. The short tourist season, July to September, yet year round costs, may have well rendered the operation uneconomic, especially after withdrawal of the dining service. The C.P.R. seemed intent on concentrating their activities in the most promising places, namely Banff and Lake Louise. Thus, in 1929, the valuables that had not been looted from the hotel were removed and sold, and the rest dismantled and the rubbish burnt. The other buildings on the site, including the employee quarters, bowling alley, laundry and station were also removed.

Today the site of Glacier House can be reached by following the old railway grade for a few hundred yards west of the bridge over the Illecillewaet river, by the campground. The area where the lawns, gardens and fountains were laid out is now a small meadow frequented by picnickers and ground squirrels. Amidst the surrounding undergrowth the stone foundations, including a couple of rusting boilers, can be found. Elsewhere bits of pottery, walkways and pipes indicate evidence of what was once an alpine resort of international fame.

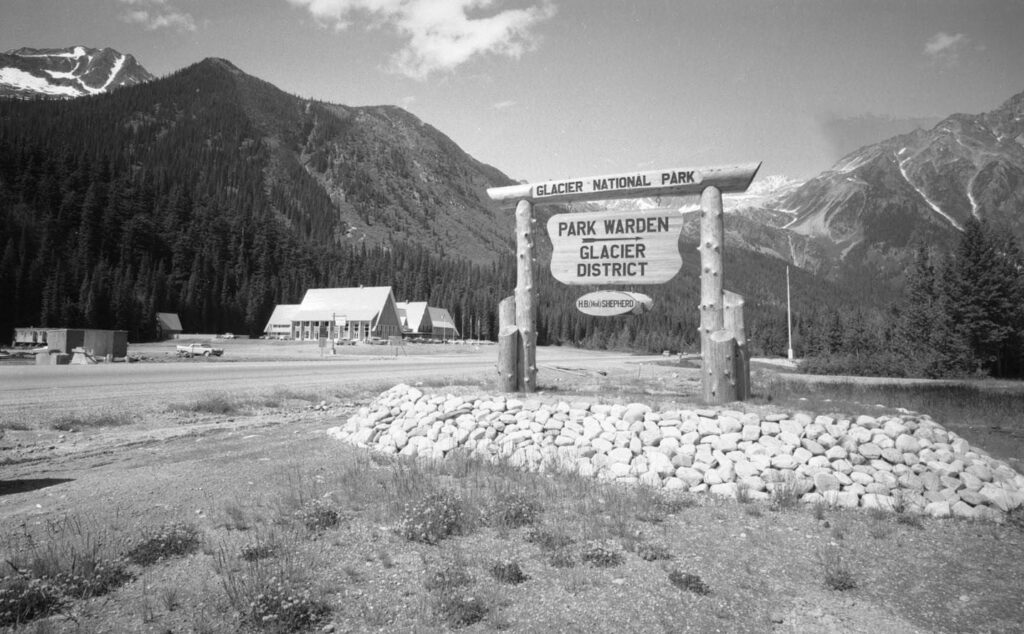

Since 1964, the Northlander Motor Hotel, just east of Rogers Pass, has provided the accommodation sought by some of the thousands who, in driving through Glacier Park, choose to stay awhile and enjoy, like their predecessors, the alpine scenery of the Selkirks.