The CPR Big Hill and Field, BC

The Big Hill

By H.T. Coleman – February 1945 CPR Bulletin

The statement that the world has no more spectacular piece of railroad than that which lies between Banff, Alberta, and the far western slope of the Rockies is not news. It has been Canada’s self-justified boast for over 50 years, and throughout that time its difficulties and its hazards, no less than its world-recognized beauties, have challenged and inspired every known engineering resource and construction energy that capable and efficient railroad builders and operators could lavish upon it. Modern facilities have eliminated the once-serious hazards, but never-ceasing skill and vigilance carry on day and night, while a vast river of traffic moves over it in both directions.

It is a vital link in the strong chain of Canada’s war effort. An endless procession of war material and fighting men pass over it and the manner in which all the traffic is being handled is news. Every mile of it is important and full of outstanding railroad history but in no part of it is railroad romance so packed as in that part of it that lies in and around the little town of Field at the base of the “Big Hill,” at the top of which is Stephen the highest point reached by the railroad. At one time the railway went higher still over grades that were all but unworkable, but that belongs to the past.

Gone now are the safety switches, and the old right-of-way has become part pf the Trans-Canada highway through the national parks. No longer does it take four puffing locomotives to hall 700 tons to the summit. Gone, too, are the roistering “boomers” of an earlier age.

A Thorough Railway Town

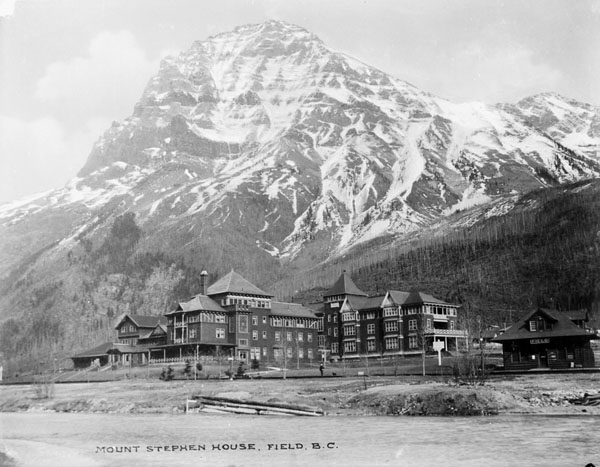

It would be hard to find a more thoroughly railroad town than Field. Division point between Calgary and Revelstoke, junction of the Alberta and British Columbia districts where the time changes from Mountain to Pacific, Field is the centre of a modest base-metal mining operation, and is administrative headquarters for four of Canada’s national parks – Yoho, in which the town itself is situated; Kootenay, which borders Yoho on the south, and the smaller Glacier and Mount Revelstoke parks farther west.

Outside of this, Field is straight railway. The Y.M.C.A., built by the company in 1902 as Mount Stephen House and intended as a tourist resort, still caters to travelers who make the town their base for tours through that lovely part of the world. But mainly it exists to provide accommodation at reasonable rates for working railroaders and their wives. To assure this the company, in addition to making the institution a direct cash grant, supplies light and water free.

Passenger crews and freight crews terminate at Field from both west and east, while engineers and firemen “bid in” from all over Alberta district on the lucrative pusher service carry the higher mountain rate of pay. Time was when nine pusher crews – that would be 18 enginemen, lived in Field with their families. Now however, only the veteran Seth Partridge, a bachelor, who started firing on the Hill back in 1907, has his permanent home at the Field “Y”. Most of the others live at Calgary, or Medicine Hat, and return to their home cities when their miles are in each month.

Town Was Bigger Then

The “bid in” system has wrought a social change in Field. In the old days, the town being bigger with so many pusher crews living here, Field was a name to strike dread in the hearts of athletic organizations in neighboring B.C. towns.

Most hated rival was the “upstart” community of Golden which had a soccer team of which it was inordinately proud. Field also boasted a might eleven, and epic battles were fought on the blood-stained Golden turf and on Field’s ground which lay in the Kicking Horse River flats opposite the station.

These games, to quote the old timers, were battles in every sense of the word. Feelings always ran high and spectators were frankly partisan. It was a poor game indeed in which a few heads were not cracked and rival players carried unconscious to the sidelines. Field’s team bore the classic title, “Butcher’s Tigers,” and the railroaders did their best to live up to that blood-curdling name.

Field’s team was usually 100 per cent railroad, while Golden’s squad was a mixture of railroaders, miners, lumberjacks and tradesmen. Golden’s leading tailor of the day, an old English international star, was keyman of the Columbia valley squad, and at least two of Field’s stalwarts were usually assigned to the task of incapacitating him.

“They were great games” recalls Billy Adamson, grand old man of the Field hill who at 76, and retired, is the picture of wiry health. Billy, an almost legendary character by weight of both seniority and fine personality, is the official historian of the settlement and is invariably called in to settle disputes. He himself played for the old Field-eleven, as did Tom Smith, stationary engineer, who is still going strong as a sports organizer in the town.

Field’s “Big Hill,” of course, apart from the town’s location as divisional point, sets it apart from the usual run of railway centres.

It would be too much to say, perhaps, that Field men are a different breed of railroaders, but there is something about these men as rugged as the Rockies themselves.

Quiet-spoken, seldom given to merely polite conversation, they take what comes in the way of tonnage and weather. Their “Big Hill” is never and easy master, and in winter it can get as cold as 40 below. Blizzards blow some times, and a “bad rail” is a constant nightmare to men who would rather face an irate spouse than the disgrace of stalling on the hill.

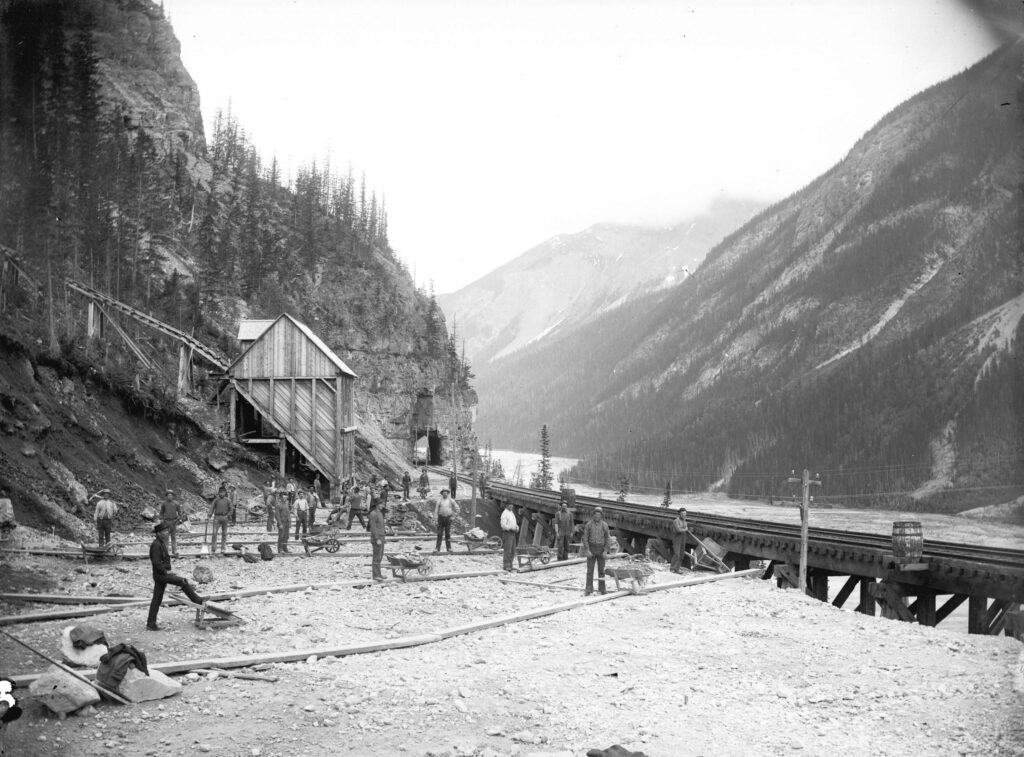

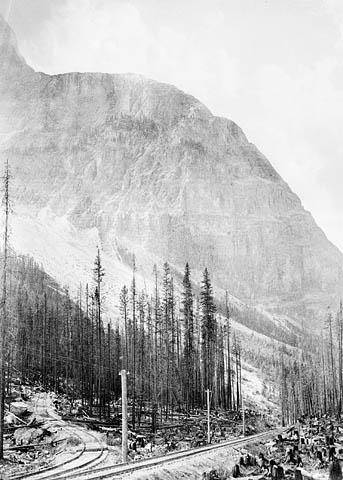

They Went Straight Up

To get some idea of the “Big Hill” it is necessary to go back to the company’s original survey of the line over the Kicking Horse pass, first surveyed by James Hector whose name is commemorated in one the hill stations. Early engineers were faced with a steep descent of the Yoho Valley and a large amount of slow and expensive tunneling if they joped to preserve the grade of one in 50 which had been laid down as a maximum. To avoid this expense of time and money, they constructed a temporary line with a grade of 237 ½ feet to the mile in a more or less direct course down the steep defile.

The old line is now the highway from Hector to Field, but in the old days trains had to be kept under most careful braking, and trap sidings were laid to catch runaway trains. To work 700 tons of freight up this hill required four powerful locomotives two at the head and two as pushers behind. To get a rough idea of what faced the men in those days it is necessary only to drive up from Field to Stephen on the highway, the old right-of-way, study the grade which calls for a certain amount of low and second grear from the best cars, and observe some of the hairpin turns and switchbacks.

Only three men still in Field remember the old hill days. Bill Adamson, of course, is now one of the “elder statesmen,” having retired; Seth Partridge, his old fireman now the dean of all the hill engineers, started in 1907, the year before the transition from the old to the new hill, and Roxy Hamilton, now well over 80 years, was a watchman on the hill before the spiral tunnels were built.

Runaway Trains

It is Roxy Hamilton’s view that the safety switches, while good enough in theory, were of little practical use in saving trains once they had really “run away.” “Runaway trains were usually going too fast, and would pile up and derail when they hit the switches,” he said, adding however, that Number One switch, near the top, saved some trains because, being near the top, they were not rolling too fast.

Veterans of the old hill, however, can be found outside of Field, but their number is dwindling with the passing years. T.H. “Tom” Crump, who was superintendent of Penticton when he retired a few years ago is one of those who “braked” and rose to trainmaster on the original hill. He remembers the link and pin coupling, the advent of George Westinghouse’s air brake, and from his retirement in Vancouver can spin many a yarn. His son, N.R. Crump, who is now Assistant General Manager, Eastern Lines, at Toronto, himself stated railroading in the roundhouse at Field in his dad’s days as an official there. Lornie Orr, well-known Banff hotelman ling since retired from the railroad, is another oft-quoted authority on the “Big Hill.”

New Hill Is Different

The present hill is a vastly-different kind of railroad. Maintenance of way men, in fact, speak of it as one of the best sections of track anywhere on the continent. All the track from Stephen to Revelstoke is 130-pound head-free rail, double-spiked and well-graded to compensate curvature and climb.

This heavy steel, biggest in use on the system, was put in with heavier bridges and other ancillary improvements to handle the T1 power when these engines mightiest in the British Empire, made their advent some 15 years ago. The T1 engines – 5900 series – weigh some 350 tons with loaded tender, distributing this weight on ten drive-wheels 63 inches in diameter. They are just short of 100 feet long and what they could do to light steel, particularly on hills where the curvature is considerable, can be easily imagined. Only slightly smaller, and lighter, are the 5800 class pusher engines, in general use through the mountains. They weigh about 280 tons with loaded tender, having 10 drive-wheels of slightly smaller diameter. Two 5800’s coupled with a 5900 road engine to haul freight trains up the Field hill are definitely hard on track particularly with their sand-blowers working all the way. They need the heaviest steel and the best of roadbed, and that is what they have.

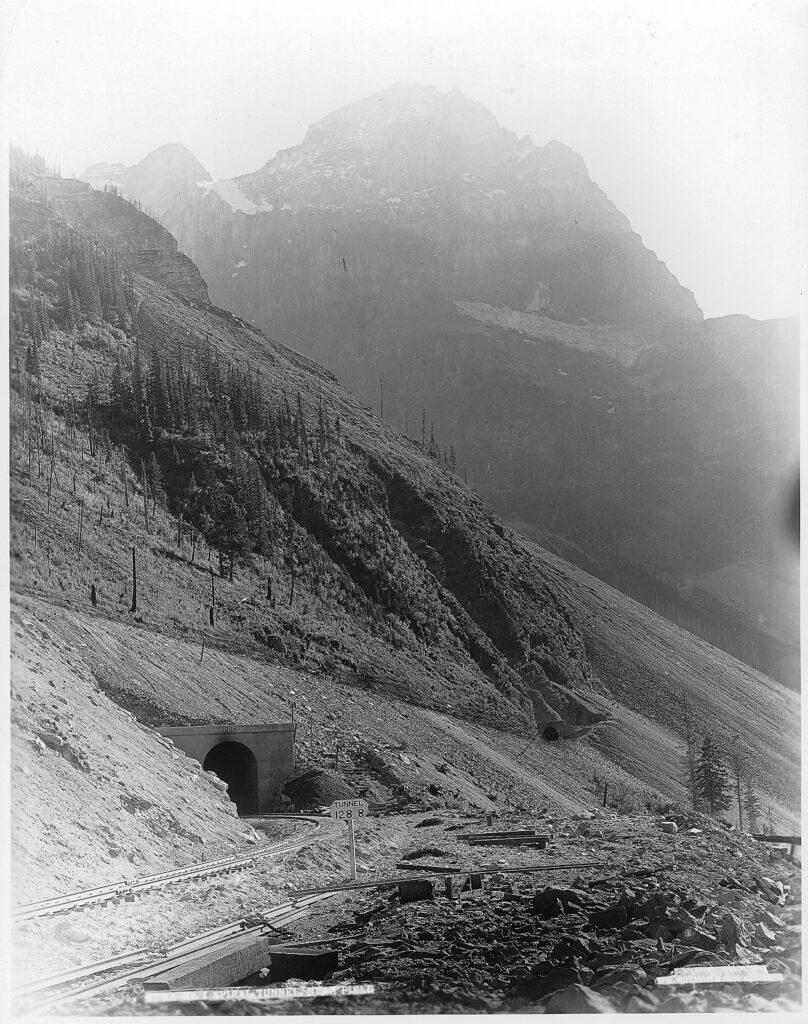

The Spiral Tunnels

Since there was no room in the Kicking Horse canyon and Yoho Valley in which to extend the line to cut down gradients, the engineers were frced to the ingenious alternative of tunneling two complete circles into two mountains to gain the length necessary to reduce the grade. Hence the famous Spiral Tunnels, railway engineering marvels of the age.

Tunnel No. 1, as the railroaders know it, from the east enters 10,008-foot Mount Cathedral for 3,255 feet, turning an angle of about 250 degrees on a 573-foot radius, passing under itself and emerging at the west portal 54 feet lower. Tunnel No. 2 through 8,806 mount Ogden has a similar radius through an angle of 232 degrees. It is 2,922 feet long and reduces the grade by 50 feet, also, of course, completing a full circle. This means that the railway travels the valley by three different lines at different elevations and crosses and recrosses the Kicking Horse river by four bridges.

Sometimes, tough it happens only occasionally and requires a train of some 80 cars, there will be a freight train on the hill long enough to demonstrate more clearly than any map or drawing the wonderous construction of the Spiral Tunnels. Given a train that long the engine will be seen emerging from one of the portals while the rear end of the train- a few cars and the caboose, will be seen entering the other portal. Such a train as this went up the hill a few years back, and the alert agent who was then at Field – George Ross, piled into his car with a camera and dashed up the hill to photograph the unusual sight. The result was a snapshot which caused much comment in and out of railway circles.

Motive Power Motif

The Field story, of course, is primarily a motive power story. With two and three engines to handle a train, pushers and crews are constantly shuttling back and forth between Field and Stephen. Some times a pusher will go over to Lake Louise to assist a westbound freight up the hill to Stephen, cutting off there to come down by itself. Pushers deadheading back to Field usually couple together at the Stephen Wye and come back in as extras west.

Passenger trains going up the hill require two engines, while freights have three, the road engine and helper at the head end and another helper pushing behind.

Road engines, 5900 series, are given a total of 1,025 tons up the hill while pushers of the 5800 series are assigned 825 tons. Thus a 5900 series and two 5800 pushers would be expected to pull 2,675 tons but in assigning the tonnage the agent, and his staff, work it out a little differently, and the tonnage would be more likely 2,500 tons or less. In assigning tonnage, they take the weight of the contents of the cars. By subtracting half of the contents’ weight from the total of the tare and allowing ten per cent, of the difference for “wheelage”, or loss of power through track friction, they arrive at the base tonnage to be assigned.

“Doubling” the Hill

Freight is usually “doubled” up the hill, two trains usually being consolidated at the top of the hill – Stephen, and taken from Stephen to Calgary by one 5900 engine. These engines are given 85 cars for the Calgary haul, this limit being set by the length of passing tracks. Actually, with the favorable grade, veteran hill railwaymen think it would be no trick for these behemoths to haul 100 cars and more.

Pusher crews figure on making two trips up the hill and back in an eight-hour shift while the engine, with changing crews, normally can be figured to make at least three round trips in the working day. It takes from an hour and 10 minutes to an hour and a half to work a train up the hill, and pushers are allowed 45 minutes for the deadhead return trip, and can make it in much less with a clear board.

To see a heavy freight pound out of Field and up the hill is an inspiring, and almost terrifying sight, for those who witness it for the first time.

Exhausts barking like great prehistoric animals, boilers literally singing under their terrific steam pressure, cylinders battened down and the motion shortened for the quick, biting stroke, the locomotives simply surge with life and power.

Experienced pusher engineers rate their iron steeds like skillful jockeys, gentling them into the turns, picking up speed in the easier spots and literally hurling them onward with every little trick of throttle, sand and quadrant.

Old timers like Seth Partridge nurse their charges with one hand on the reversing gear and the other on the sand valves, for they use sand every step of the way, particularly in the tunnels where the water leaking down the tunnels on to the track might give bad rail. Those unfamiliar with the operation of a steam locomotive find it somehow hard to believe that, without transmission, engines can be “geared”. But it’s low-gear work on the Field hill and the really sound engineer makes intelligent use of the quadrant, setting the Johnson bar down in what the hill-boys call, “The OCS corner”, for that shirt, choppy stroke which gives considerably less than the fill travel of the valve but spells POWER in any language.

Pusher crews are on the strength of the Alberta district, as are the sectionmen, watchmen and operators who maintain and protect the tack and traffic. The Fireld terminal starts at the east switch and is on the British Columbia district. Terminal employees are thus B.C. district men and work on Pacific time while the pusher men and others on the hill set their watches for Mountain time.

Difference in Time

It is a little disconcerting to the newcomer until he gets used to it, to find hill men talking in Pacific time. This, however, marks the only discernable difference between the men of the two districts who work in complete harmony. In fact, it is hard to realize, except for the time difference, that Field is the junction of two districts.

There are many well-known old-timers there. Among them is Pete Litva, the night yardmaster. Fred Barlow, assistant agent, is a young man, raised in Field who is just back to civilian life after two years overseas with the R.C.A.F. Barry Robeson, first trick operator; Johnny Ashdown, on the second trick, and Dave White on the third trick, are all experienced mountain men.

Track Well Patrolled

Probably no section of track on the system is more constantly patrolled, more safely guarded than the 14.4 miles between Field and Stephen. Track patrolmen are stationed all along the way covering every mile of the sections on a 24-hour basis. At the intermediate point of Yoho, an operator is on 8-hour duty, clearing traffic, while Stephen, at the top of the hill, and, of course, Field itself at the foot of the hill, have operators on three-trick basis.

Truck patrolmen, like their brothers in the section service, are a hardy and devoted lot, inured to the tough weather, alert to contingencies in clearing track in case of obstructions. In such steep canyons falling rock is a constant menace and in this respect watchmen render yeoman service.

Typical of the devotion to duty displayed by watchmen is the story of George Sacaliuc, Russian-born watchman at Yoho on the downward end of the hill. George’s section lies beneath the frowning cliffs of Mount Stephen, and there are several places, one in particular where rock slides have given trouble.

One night last winter in a howling blizzard George found an obstruction on his section and, as is the habit with mountain watchmen and sectionmen, he set about in his own way to clear it. The force of the wind, however, carried away his mitts as he was engaged in this task, and the result was two badly-frozen hands. They were so badly frozen, in fact, that the doctor found it necessary to pull all of his fingernails, and even now the hands give him trouble.

In league with the section and track patrol forces is Hughie Reid, the signal maintainer. In the 15 years he has been on the Big Hill, Hughie has become one of Field’s most useful citizens. A born organizer with a likeable personality, the little Scot is into everything in the railroad town. The curling club where the townspeople find healthful recreation on two well-kept sheets of ice, is debt-free and booming. Hughie has been its secretary since it was formed. He took a leading part in setting up an open-air skating rink for the children on the Kicking Horse flats; he is active in church work and was for a long time one of the board of the YMCA. A few years ago, before Field’s young men started leaving to join the armed forces, he was one of the mainsprings behind the local hockey team, too.

Block Signals Help

The whole hill is protected by automatic block signals of the absolute permissive type and the installation adds a further measure of safety. Signal maintenance on this rugged terrain, however, is not without its hazards. More than once Hughie Reid has been treed by a bull moose which mistook his innocent speeder for a rival lord of the forest.

Slides, too, can play havoc with delicately-adjusted installations. At one place which developed trouble the ingenious Hughie developed a “burglar alarm” system of his own. This he did by putting in a set of wires strung on short poles for the distance of about 50 yards on the high side of the tract at the foot of the slide area. Any heavy object coming down the mountainside touches these wires with sufficient force to break the circuit and throw the board down.

The trap worked fine, Hughie said, until one night some wild animals adopted the wires and poles for a scratching place, thereby dropping the board and leading to a certain amount of fervid cussing.

Field’s most famous slide, of course, is the one which came down over two levels of the track, wiping out the station at the pint then shown on the time card as Mars. This was the occasion when Billy Adamson, returning at the throttle of a pusher engine, was coming down the hill. He saw the slide, the damage it had done, and the further damage it might do. He stood by his engine while his fireman, Seth Partridge, clambered down the precipitous sides of the canyon to warn the operator and call out the gangs.

Brave Deed Remembered

It is only fitting that the present station, replacing Mars, now shows on the time card as Partridge, commemorating a brave deed by a fine engineman.

Roadmaster Alf Ades is a newcomer, from Edmonton, to the Laggan subdivision where he is now in charge of the track between Cochrane and Field. He has had extra gangs changing out steel, relining curves, laying new ties and doing other important work, and the track is now in excellent shape.

Locomotive Foreman Joe Frost, in charge of the mechanical department at Field, has 10 locomotives assigned to him for service and maintenance. These consist of six hill pushers and four engines assigned for pusher service farther west on the Golden Hill…Golden to Leanchoil. His roundhouse also makes running repairs when necessary on the 5900 road engines which turn around there. These engines, of course, are maintained at Calgary and Revelstoke, but occasionally one of them will need attention at Field.

Mr. Frost has three machinists looking after running repairs on pushers, and a machinist on maintenance repairs of these engines, as well as a miscellany of 32 other fitters, helpers, hostlers, stationary firemen.

Roundhouse Supplies Light to Community

The roundhouse supplies light to the whole community, also heating the YMCS, company houses occupied by staff, and company buildings. Fred Woolley, car foreman, has a staff of nine carmen, a helper and four laborers, two of them extra summer help.

Handling 18 trains daily, including the main line passengers, it is a main-sized job for the carmen.

Living in a national park which is a game preserve, it is not surprising that most of Field’s 350 residents find their pleasures in the simple things. Fishing would rate as Number 1 sport.

On every side is incomparable trout fishing. Not far away, off the highway, is Emerald Lake where the company’s chalet now closed for the duration, caters in normal times to tourist visitors. Emerald Lake is noted for trout fishing and today several Field residents maintain boats there from which to angle. Near the top of the Field hill, where the railway and the highway run parallel, is Wapta Lake, site of another of the company’s bungalow camps. These waters are also liberally stocked with trout. Another eight miles in from Hector, or Wapta, is Lake O’Hara, another company bungalow camp which boasts good fishing.

Hangout for Grizzlies

Sherbrooke Lake, a few miles northwest of Hector on the Great Divide is celebrated for fishing but the natives are giving it a rather wide berth because it is a hangout for grizzly bear. It was near this lake that Nicholas Morant, the company’s special photographer, and Chris Haesler his Swiss guide from Lake Louise, were attacked and terribly mauled by a large female grizzly, in September, 1939.

Last summer the wardens killed an eight-foot grizzly in the same area. Fortunately, of course, grizzly keep well back from settlements and are not a serious menace. Black and brown bear on the other hand, are pests but Field citizens have devised effective and direct means to send them packing.

Being chiefly a railroad town, but situated in a national park and set up under federal law without a town council, it is not surprising that company men play a leading part in community affairs. School concerts, socials, dances and other activities are attended by employees and their families.

The local magistrate is William M. Brown, a carman, who spent the past 15 years in Field. It is a position which the tall, sport-loving Fifeshire Scot fills with dignity and good judgement. Lawbreakers are few and receive swift and impartial justice.

A Canine Brakeman

Magistrate Brown on his rounds through the station yards checking equipment is accompanied as a rule by Tom, a non-descript but sagacious dog. Tom is as much part of the railroad around Field as the roundhouse. He has a remarkable nose for hot-boxes and will “freeze” beside one until his friend, Magistrate Brown, comes along to do something about it. Tom leaps nimbly on to the running board of the switch engine, climbs up on the tender and is so much at home around the right of way that the Field local of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen have made him an honorary

brother.” As if conscious of this distinction the dog, while willing to share food with train crews in the caboose, scorns a dining car handout as being beneath his dignitary.

The Ski Jump

Field’s other monument is the ski jump facing the station from the opposite side of the Kicking Horse River, distinctly visible and readily identified the slide, gouged from the side of Mount Burgess, is rapidly going back to the bush from which it was cut, now that its creator, Nels Nelson, is no more. Nels won his great fame as a daring and skillful jumper at Revelstoke where he and other intrepid Norsemen built and operated the famous “Suicide Hill.”

Nels in his later years had the misfortune to lose an arm in a mishap. A trainman up to that time, he then found employment as train baggagemen and ran between Kamloops and Vancouver.

All in all, Field’s railwaymen don’t consider themselves badly off. It is a beautiful place to start with. You hardly even see a mosquito, for example, and even in the hottest part of summer the nights at 4,000 foot altitude are cool and you need at least two blankets. In the fall when the trees change color, the canyon changes its whole complexion with it. The winter snows aren’t as deep as some farther west – at Glacier, for one – and while occasionally blizzards blow, the winter days for the most part are full of sunshine and crisp, invigorating “dry” cold. Nature is always close at hand.

“Sitting On Top of the World”

And there’s some satisfaction in knowing that Stephen, at the top if the hill, is 5,337 feet above sea level and the highest point on the main line, and that when you climb from Field to Stephen you are climbing 1,265 feet in 14.4 miles. That in itself sort of gives one the feeling of “sitting on top of the world.”

Yes, Field is a place that gets into the blood. As one veteran engineer put it – and somehow it seems to tell the whole story… “I have been going up and down this hill for 37 years, and each time it looks different. If the day ever comes when I can’t get a thrill out of this country, I hope the boys will lay me away quietly. And besides, were can you get fishing like it.?”