The Mountain-Wise Disaster-Trained Railroaders Saved the Widow’s Home

From the Daily Colonist, November 15, 1964

By Edmund E. Pugsley

“I have seen many ghost towns since I came to Canada from Sweden in 1889. And I have read of many others in this morning boom province of British Columbia. But I have never read about one that was so suddenly and completely wiped out as was the little ghost town of Donald on the Columbia River in August, 1909.”

That’s how John Anderson, the veteran CPR roadmaster, summed up the cremation of Donald, 54 years later. It requires more than ordinary scenes to live so vividly for so long in one’s memory. John Anderson had a wealth of such memories, and with good reason. You didn’t give battle for 23 years against the great white on that old, trouble-breeding hump of Rogers Pass without having death breathing down your neck on many occasions. And that kind of association eight months each year develops a fraternity that deepens with the years.

But only those who have been through it can know how or why the memory of a row of windowless, ramshackle cottages can grip the throat half a century later.

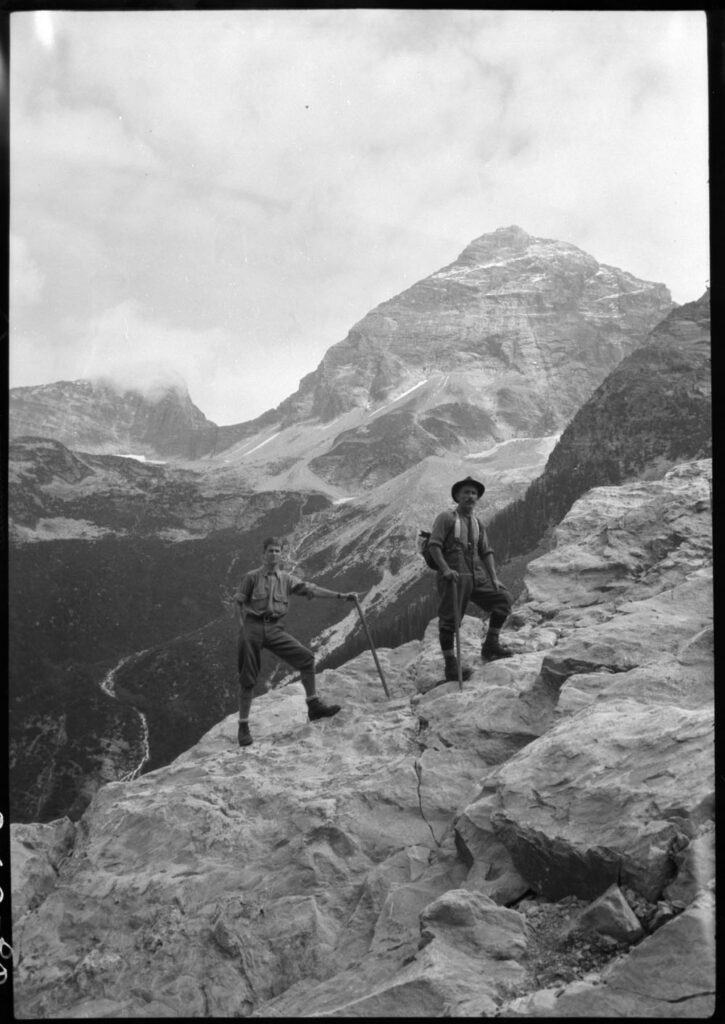

Donald Smith, the grey-bearded, frock-coated, top-hatted dignitary, who hammered down the famous Craighellachie spike which made the Canadian Pacific Railway a reality while much of the world scoffed, had two significant mountain locations named to his honor.

Credit: Library and Archives Canada/PA-058226

One, the God created, glacier-crowned Mount Sir Donald that dominates the Selkirk peaks at the source of the Illecillewaet River – will endure forever.

The other, a bustling, drama-packed man-made railway town beside the Columbia River, became suddenly a ghost town, then 10 years later, a long, thin trail of ashes.

Actually, there was a third memorial, more in the nature of a sequel. This was a cube of the blue granite that was drilled from the base of Mount Sir Donald, 16 years after Lord Strathcona’s death. This was trundled by stoneboat to the railway at Glacier station and shipped across the continent to form the cornerstone for a memorial building on the Yale University grounds, New Haven.

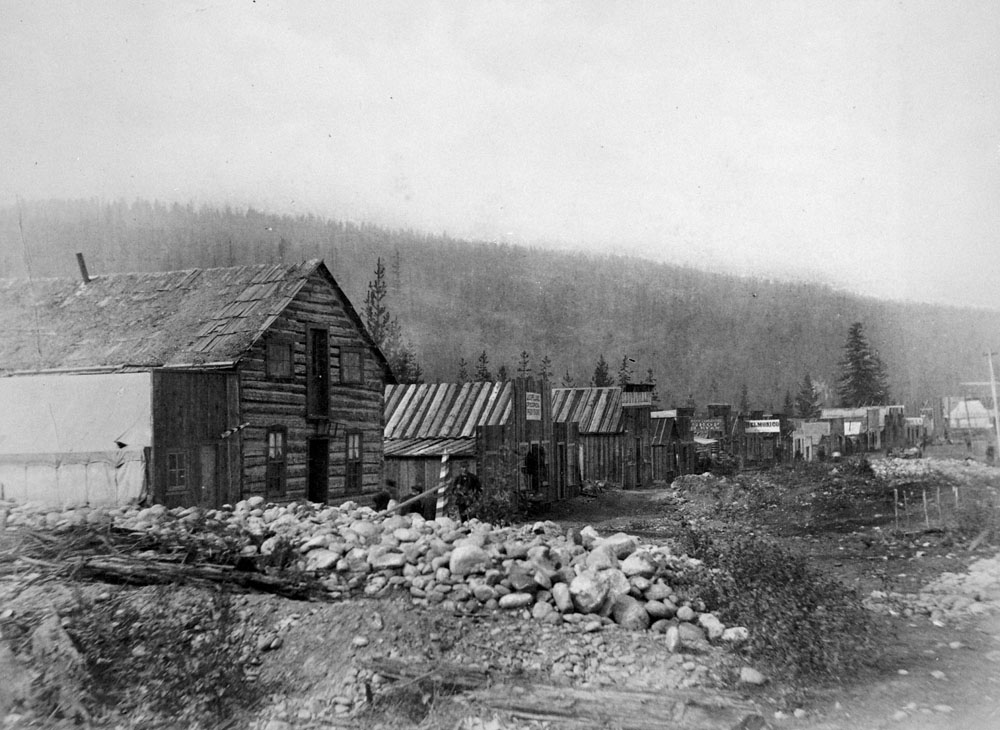

Donald town will probably be best remembered for its casualty list amongst railroad men during construction and early operation days up until 1899. It was a long, straggly town that commenced with the water tank on the east, and ended some three quarters of a mile westward with the cottage of widow Minnie McBride and her two daughters. In between these, the railway had its roundhouse and shops and station building, and the government its public affairs quarters, and then there were churches and a school and saloons and stores and hotels and restaurants and homes.

This was Donald in the late 1890’s when John Anderson met a brother at a tie-cutting camp about five miles east of Donald. Then, on April 1, 1890, the two brothers hired out as trackmen on the CPR at Beavermouth, 11 miles west of Donald, where a third brother was already employed as track foreman.

From Beavermouth they trudged the tracks from supplies, and dallied for cheers along the lamp lit plank walk and through the swinging saloon doors, which were the main attraction until one came under the influence of the ladies auxiliaries to the railway brotherhoods which provided more home like entertainment. It was in these saloons that Sheriff Redgrave dispensed law and order law and order and Fr. Pat Irwin, the Anglican missionary, spiritual comfort, with occasional sermons and music by his melodeon organ, carried on his back.

And it was the big car shops whistle that put the chill in the spines of the women and sent them scurrying into little groups to watch their men answer the call for all hands to man the “wrecker” train, trying to comfort the wives of the trainmen who had gone out over the Pass. It might be many hours until they learned how many of these were buried under a slide, and which of them the old Snowman had selected this time as his victims.

“Donald was, for me, a very friendly, law-abiding town,” John Anderson recalled. “All young people. Yet I never saw one fight or brawl in all my visits. Sheriff Redgrave patrolled the street, or mixed with the crowds in the saloons, enjoying himself with them. If a man would get overloaded and unable to navigate under his own steam. The sheriff would just lock him up for the night and let him out in the morning. It was very seldom that anyone was brought into court and fined.”

Two large sawmills at Beavermouth provided further patrons for the stores and salons of Donald. Workmen at these mills lived in company boarding houses in summer, then went into logging camps for the winter months for further logs. And that was how it was in the Donald area up until February 1899, following the dry slide that swept away Rogers Pass station on the last day of January with the loss of seven lives including the agent and his wife and two small children.

Then suddenly an order came through for the mass movement of the entire railway facilities from Donald to Revelstoke, 78 miles across the Selkirk Mountains to where the milky Illicillewaet River tumbles into the staid Columbia. This 78-mile hump of trouble that saved the fortunes of Stephen and Smith by trimming some 50 miles of trackage costs from the Big Bend of the Columbia at the critical stage of CPR construction, with the discovery of Rogers Pass.

The Columbia looks tired and thirsty here as it pauses to lap up the cold, fresh Illicillewaet. And it gives little indication of its own escapade since parting from the railway at Beavermouth – the escapade that took it galloping away up north into the heart of the ice field, where it didn’t like what it saw, and suddenly swung around to head south again. And this is the scene where deddling man will soon be changing the old river’s physiognomy from unbridled abandon to a placid 80 mile lake to furnish more power and water for our neighbors south of the border.

In the bewildering exodus from Donald. That February of 1899, tradesmen in private business were offered free transportation of material to either Revelstoke or westward to Golden. Few of them took advantage of this. Lumber was cheap, and old material would not be serviceable, except for some of the windows.

On their part, the company tore down all their own buildings and shops, pulled up trackage, except for two main line sidings, burned all wreckage and “leveled off the ground like a football field,” John Anderson remembered.

The years passed. The old river flowed silently on. The wooden buildings bowed and sagged with age and neglect, and the weight of snow on their roofs or drifting in through holes that once knew windows and doors. The joints creaked and sprung with frost and ice. Passengers being carried past might cast curious glances at the sad ghost town, but the railwaymen who had living memories lingering there dwindled. And John Anderson moved on in the service to the position of roadmaster, with headquarters at Field, down there at the foot of the Big Hill of the Rockies with grim Mount Stephen glowering down from its two-mile height, and showering everyone and everything with its stinging sugar snow through the long winters.

Came the summer of 1909. The Big Hill was now remodelled with air of circular tunnels that stretched into steep four mile 4.4 grade into an eight-mile maze and a 2.2 grade. And John Anderson, the roadmaster, was taking into the August sun on his little hand speeder, westbound on a periodical inspection. He reached Golden, where old Columbia had been gulping the Kicking Horse River for ages before explorer James Hector of the 1858 Palliser Expedition was awarded a kick from his won horse and decided to commemorate it by naming this romping river for the occasion. Here John stopped over for the night.

Continuing westward next morning, the roadmaster reached the ghost town of Donald about 9:30 and was greeted by flames leaping 75 feet high from the extreme east end. Repressing his personal regret, he turned his practiced, trouble-seeking eyes along the scene, assured himself there was no danger to railway property, and then turned to the lone cottage, half a mile westward on the extreme end of the old town. Here lived the only residents, the widow Minnie McBride and her two grown daughters. And here he was needed.

He reported the situation to both Revelstoke and Field, saying he would take the local section crew down to the McBride home and see what he could do to help protect it. Arriving there with four men, he found the three women had already packed their suitcases with personal effects and were carrying out some of the lighter furniture to a safe distance from the house. John advised them to leave the heavier things for the men to carry out if and when it became necessary. But first, they would try to save the building.

A brief study decided them to use the back-fire plan. The crew took their handcar half a mile westward to the river bridge and filled four barrels of water. With this for a stand-by against falling embers and sparks, they set about pulling down the cottage that stood next to them – a frail, dilapidated shack. Gathering some old telegraph wire, they rigged this to the ridge timber and formed two teams to pull and haul alternately until they had rocked the rickety walls into collapse. A match to the tinder-dry boards soon set them up in the fire-fighting business in dead earnest.

Meanwhile, the women had found some old lineman poles and fixed mops on the ends of them. And now they were dipping these into the water barrels and sponging out sparks and embers the moment they landed on their house. The men patrolled the roof with make shift ladders.

It was a hot contest and every glace toward the raging flames to the east brought new doubts and fresh efforts. Only the fact that the buildings were all strung along in a single rambling line gave hope for success. Urgency developed rhythm of action. And by the time they had a second building reduced to ashes and a third one fired, they decided they had enough cleared space to let the back-fire take its course in the wind that had veered mightily in their favor. Beyond this space – about 200 feet – they stood their ground in teams, taking time for a hurried lunch.

The afternoon wore on with the fire-fighters dividing their time between dousing falling embers and watching the two fires sweep toward each other. By 4 o’clock they had joined and soon the last roof fell in with a mighty shower of sparks and embers. The battle was over, and the McBride home had been saved.

But the long line of empty, ghostly buildings was gone and now the three McBride women would be alone. And the few oldtime railwaymen who would pass would find nothing but their memories. Minnie McBride swung away from the scene, dashed a hand across her eyes and ducked into the house.

By 5 o’clock the men were carrying the furniture back into the house. John Anderson stood staring at the scene until he, too, was awed at the tremendous change in the picture that left the river bare and lonely now in the soft summer evening. Even a ghost town was something to look at.

And suddenly he was recalling the countless times he had passed along this railroad during the past 10 years, remembering something different from the days when it was filled with active men, women and children. They’d been gone for 10 years, but they had left a bit of themselves in those simple little cottages. Now all this was wiped out, and only a scant few would remember how they stood side by side in the struggle to keep this single track bottle neck open for the rolling wheels of traffic east and west.

The roadmaster was arranging for one man to stand watch through the night against a possible stir of the embers. In a breeze, when a westbound freight slowed to let Assistant Superintendent T.H. Crump drop off. He advised the roadmaster that another eastbound train would stop and pick up the officials. This gave Mrs. McBride time to make tea for all hands, fussing the whole about paying the men for helping her save her house. Of course they declined.

She then suggested some souvenir to give them. And when this, too, was firmly declined, one of the girls noticed how both officials had examined curiously the homemade clothes drier attached to the kitchen wall behind the stove. This the girl removed with a screw driver and passed it to her mother.

After constant nagging, that she must give someone something, or she’d never sleep all night, Crump took a silver dollar from his pocket and winked at John Anderson. “Heads I win,” he said. “Tails, I lose.” He tossed it. Minnie McBride insisted that John carry off the trophy. He eventually gave in. And today that very useful kitchen fixture does valiant service in the Anderson Victoria home, after 55 years.

Doubtless the McBrides found their cottage unbearably lonely now, especially the younger two. Before winter had set in again, they moved to Golden. From there, Mrs. McBride kept in closer touch with a farm she owned near Moberly, with a man named Couper running it for her, raising chickens, pigs, cattle, and vegetables, with enough oats to feed the stock. The owner made two trips a week to keep the farm supplied and train crews would let her off at her place.

Bit in time she moved away and disappeared with her memories.

“One of the first to settle in Donald and surely the last to leave it,” John Anderson mused.

John Anderson was transferred to the E & N road on Vancouver Island in 1913, two years before the five-mile Connaught Tunnel detoured the old Rogers hump and left it to the grizzlies and snows and forest rangers. John finished out his long railway career on January 1. 1937, enjoying quiet retirement for another 27 years in Victoria, for a grand total of 92 years and 10 months.