Big Bend Gold Rush

Mining in the area that we know as Big Bend Country was underway as early as 1864 but the chief activities took place between 1865-66. The following report from the Daily Province, Vancouver, British Columbia, Saturday, February 18, 1922, covers some of the mining activity and who was involved as well as the history of the naming of some of the creeks.

Barring the Fraser ‘excitement’ of 1858, the biggest gold rush in the history of British Columbia was to the Big Bend of the Columbia. Men who were there, still living, happily, say there were no fewer than 5000 men in the Big Bend country in 1866, and the yield from 1865 to 1867 must have been at least $8,000,000. The story, condensed, is told in the three following extracts:

From Dr. Dawson’s “Mineral Wealth of B.C.”:

“In 1865, a number of miners from the Kootenay district were prospecting in the neighbourhood of the “Big Bend” (of the Columbia River) country; the report of their success resulting in the Big Bend excitement of 1866. This subsided almost as quickly as it had arisen, the number of men who rushed to the place being much too great for the opportunities of work”

From the first report of the British Columbia minister of mines, 1874:

“In 1865-1866, great excitement was aroused by the discovery of gold in paying quantities on the Big Bend of the Columbia, known as the “Big Bend Excitement.” Miners from all parts flocked in considerable numbers to the new locality; steamers were built and roads, at great expense, opened, to encourage traffic; but before twelve months had expired “Big Bend” was deserted, and now discoveries in Omineca claimed attention. The original promises of Omineca, after three years’ preserving work, have been fulfilled.”

From “Mineral Resources of B.C.” by D. Oppenheimer, mayor of Vancouver.

“In 1865-1866, Big Bend was the scene of great excitement through its fold discoveries. Before twelve months it was deserted. The cause was the simmer water rise on the surface diggings in narrow confined creeks. It is generally conceded that gold placer diggings in the Big Bend are more plentiful and more generally distributed than in any other portion of West Kootenay.”

In Revelstoke there are men who since the C.P.R. crossed the Columbia, have, like Mayor Oppenheimer, spent thousands in recovering thousands, but failing to make ‘pay’ because of want of organized capital and the physical conditions prevailing, such as pitching bedrock, bouldered channels, flooded streams and high transportation. Money and machinery, science and system, will alone unlock the Big Bend box. None of these keys the placer digger had. Unless diggings paid at least $10 to the hand, daily, and paid it quickly, they were not white-man’s diggings – and Big Bend, as others before and after it, became a place of old memories and the Chinese.

Early in 1865 the British Colonist of Victoria published news of new gold fields north of Wild Horse. Miners from there at Walla Walla declared it ‘humbug.’ This made Bancroft, the American historian, followed by Dr. Dawson, and others, say Big Bend was from Wild Horse. A reference to Constable Young’s letters, Dec 1, 1864, and Jan 10, 1865, discloses that ‘rich humbug,’ reached by very few, to be Canyon Creek. What most probably happened is, that finding ‘colors’ but traveling difficult, and Wild Horse taken up, Canyon Creek miners returned to Walla Walla for the winter; and in spring started up an open Columbia River northward. Records show then finding gold at Fort Shepherd, Salmon River, Slocan River, Fish River and all the Columbia bars below and above Revelstoke. For years their workings were to be seen on Begbie Creek, Jordan River flat. Revelstoke Rapids and on to Big Bend. This is confirmed by the word of one member of the steamer ‘49’ crew, still living at Revelstoke. The fact that Carnes Creek, the most southerly of Big Bend paying creeks, was first found (by Carne, a Cornishmen), helps prove that discovery made from the south and not around the Bend, from the north.

In June 1865, reports reached Victoria, repeated by arrivals from Colville, that 200 men had gone up the Columbia to Big Bend, and that the river looked like the Fraser in ’58, so many boats, canoes and even raft scows were on it. At Death Rapids rich diggings were said to be had, twenty-five cents to one dollar per pan. In July the Colonist reported ‘Mountaineer’ Perry, Walter Moberly’s field assistant, as saying that miners there were taking $700 each every few days, and he, himself, was reported as taking $100 a day. Stone, the expressman, visited the new camp in August. He found two miles of ground and 120 men on French Creek. The discoverers were four Frenchmen (hence French Creek) who located in the spring of 1865 on finding $16 in eleven pans of ‘dirt’. R.T. Smith, the gold commissioner, went in too, leaving in November. He reported the know yield of French Creek as $32,000; McCulloch, $27,000; Carnes, $3000.

“But,” says Bancroft, “on account of the gold export tax then in force, it was understood that not half of the gold taken out was reported.” Bancroft is right. Gold Commissioner Smith’s figures totaled, divided by the number of men (say 200), and the time of digging, (say six months), would give each miner about $31 a month or $1 a day. Could such a dividend cause the rush of 1866? Unlikely! And no one believed it, even in Victoria and New Westminster.

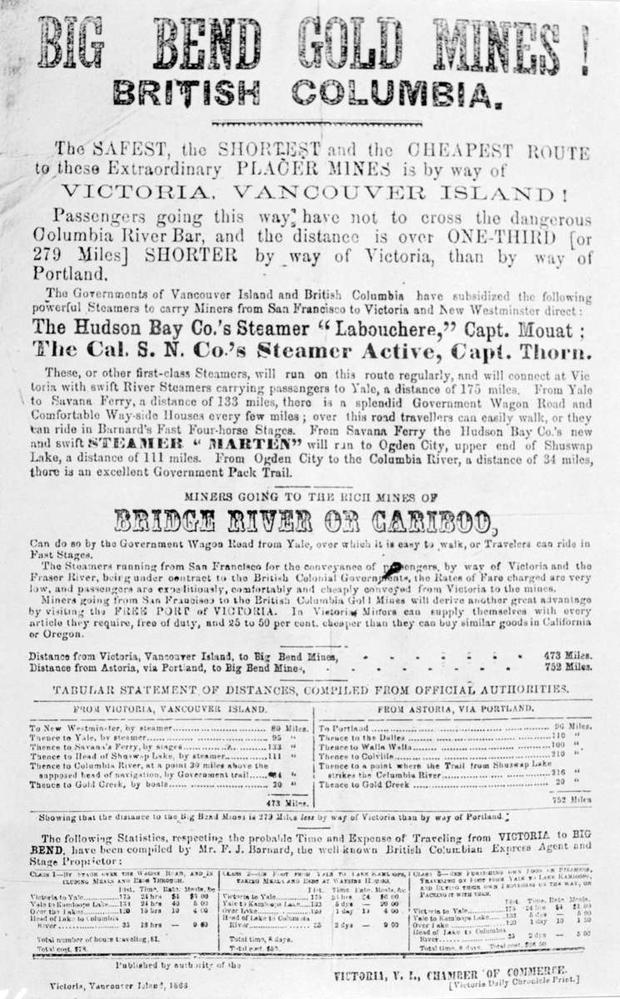

The news of the new gold field was wildly welcome to Victoria, which flourishing Cariboo and free trade had made the chief trading community of the colony. Cariboo was at its peak in 1863-1864, and its decline plunged overstocked Victoria into despair. Wild Horse had not caused a ripple there. The ‘key to Kootenay,’ (the Dewdney Trail), would not turn, and the ‘traders from Colville’, rifled the trade chest. This was not to happen again; it could not be afforded. With talk of ‘union’ amongst the discontented; with New Westminster, capital, and strengthening her hold daily by trade and revenue, (Big Bend receipts at its best were ‘not less than $1000 a week’), and with Portland also in the race, it was indeed time to ‘hustle’ if commercial and political supremacy was to be retained. Accordingly, an advertising and development campaign of intense effort was begun. Big Bend was called the greatest gold field yet. The two Colonial Governments, advised to take lessons from American enterprise, responded. Ocean vessels, the ‘Labourchere,’ (lost on her first trip), and ‘Active,’ were subsidized to run to British Columbia from San Francisco and other American ports. The Cariboo Road was extended from Cache Creek to Savona’s Ferry on Lake Kamloops. At Chase, the Hudson’s Bay Company built the steamer “Marten,’ the first British-built bottom of B.C. inland waters, to ply between Savona’s and Seymour (first called after Peter Skene Ogden, ‘Ogden City,’ or ‘Ogdenville’) on Shuswap Lake. From there the trail of 1865 was re-cut, and extended to the mines. Billboards and newspapers advertised the route; correspondents were sent out, and the ‘rush’ was on in earnest.

So eager were men and merchants to get in, that ice on Lakes Kamloops and Shuswap had to carry them and their goods, on snowshoes, with sleighs, sleds and toboggans. One character, “T’ousan’ Dog Joe,’ alias Telias, with a seven-dog sled, mushed up a small fortune. When the ice broke, boats of all kinds, safe and otherwise, took hundred to Seymour. When Moberly, the government agent, sent to make a trail to the Columbia, got to Seymour in April, 1866, an impatient crowd awaited him. One wouldn’t, “Old Bill Ladner” of Delta the father; he cut his own trail for a carload of goods, and made an early cleanup.

What was happening on our coast was working like yeast in Portland, Walla Walla and Colville, on the Columbia River. Portland advertised the lower river and the overland routes by the Okanagan and Kettle Valleys; an open river from Little Dalles or Colville. At Littles Dalles (just below the boundary), a steamer, the “49”, was built in August, 1865. She crossed the ‘line’ on April 10, 1866, the first steamer to operate on B.C. Inland waters – the “Marten” left Savona’s May 26 – and miners and merchants poured in by river and trail to her. The race was on; and every month of the spring and summer of 1866 added numbers to the throng. What policy the Marten used is not discoverable, but Capt. White of the “49” from the first, resolutely refused to carry any man who could not pay his fare and had not a grubstake, and took out, gratis, every man returning “broke.” About three-fourths of those leaving Big Bend in November, 1866, would not pay their fares to Colville.

While it lasted it was a wonderful rush, the population ran to thousands; the miners did well. Dupuis Hill claim, on French Creek, was said to have yielded $2500 in one week. The Thompson, Ridgem Guild and Black Hawk (a tunnel mine), and the Lafleur (a drift claim), all did well; but the star claim on French Creek was the Half Breed, which for a time yielded $100 per day to the hand. French Creek was to Big Bend what Williams Creek was to Cariboo. McCulloch Creek was, next to French, the best producer, and the discover and Clemens made big money. Carnes Creek was third; and Smith, Goldsteam and others followed up.

Mr. Oppenheimer estimated the yield for the short season of 1866 (a year of floods) at $250,000. About $100,000 each to French and McCulloch Creeks. The pay area was too small. Pitching bed-rock, found at six feet at one place, and not at sixty in another, and big boulders in the channels, left the depths of these creeks unexplored by poor men in a hurry. In spite of the exodus, 100 men wintered in French McCulloch in 1866-67. For years afterwards the “49 Co” (the steamer syndicate), worked Carnes Creek; and after them Capt. A.L. Pingstone, her mate, continued it. The Chinese came in 1871; but it is noticeable that when the railway arrived in 1885, while the Chinese outnumbered the whites at Wild Horse two to one, all the miners in the Big Bend were whites. The early whites had left nothing shallow, and it would require a purse and patience to plumb the unworked depths of the Big Bend.

The chief towns of the Big Bend in the Sixties were Kirbyville, near the mouth of the Goldstream, and La Porte, at the head of navigation on the Columbia below Death Rapids. They were lively places. For years, in the Nineties, a billiard table from La Porte was a feature in the reading room of the Central Hotel, run by Abrahamson Brothers, at Revelstoke and the prospectors of post-railroad days, often played more than a piano in the deserted “palaces” of thirty years before.

With government’s joint aid and enterprise, the “traders from Colville” carried away the “bacon.” Toll-roads, stages, mule-trains, plus the little “Marten,” could not, with tariff aid even, fight steam on an open river. Nothing but a prohibitory tariff could have conquered Columbia; and that kind of tariff might be a boomerang to a non-producing B.C. Had a road, a free one, been run at first from Sicamous through Eagle Pass, which Moberly discovered in 1865, B.C, merchants might, from Revelstoke, have competed with the “49” and Colville, Portland’s drummer and base.

The Seymour trail was poorly, cheaply chosen, and proved entirely inadequate to our traders’ interests. Rivers versus trails, steam versus stage. We lost! But not without trying; and the lesson was momentous. Vancouver Island, seeing B.C. gold fields going to the Rockies – a bigger B.C. than Cariboo, and more remote from seaboard influence – resigned representative institutions for Crown Council control, free trade for a traffic prop, and took up her part of a tax three times bigger than her own. It was momentous, too, in that it showed B.C. the need of money and power to build more than Dewdney and Seymour trails. It showed that if steam was to be a factor, then steam B.C. should have. The colony could not expand on a revenue of road tolls, in and out tariff taxes and miners’ licenses. These might do for a civil service list, perhaps, but for expansion and the winning of trade, no. And so there came about – Confederation.

It is interesting to recall that Walter Moberly, when on his preliminary railway survey, began on the Columbia River with headquarters of Moberly, near Golden, on the river’s east leg and at Big Eddy, the mouth of Eagle Pass, opposite Revelstoke, on its west; and that he charted the “49” of the days of 1865-66 to carry supplies to his Big Eddy camp, those for Moberly going over the Wild Horse miners’ trail from Walla Walla.

It is of interest, too, to note that “special” Big Bend news items to the Colonist at Victoria were sub-headed “by electric telegraph,” “by Collins Overland Telegraph.” The Collins company spent three million dollars in B.C., taking wires through to connect with Siberia and Europe, upon the failure of the first Atlantic cable; but the news of the success of the second cable, (June 26, 1866), made the venture useless as a whole.

If Captain Pingstone is alive, (he was in 1910), and Mr. J.P. Null, rancher at Ducks, (he was, 1895), they probably form with Mr. J.C. Montgomery of Revelstoke, the only survivors of the crew of the steamer “49.” Captain Mouat of the “Marten” died, it was reported, at Fort Rupert on April 12, 1871. Of the other members of the Marten’s crew no information had been gleaned.